Imagine feeling that you are neither male nor female. You don’t feel like a man or a woman, you don’t want to become a man or a woman and the binary construct of life means that you are excluded in everything, from toilet doors to tax forms.

For Vic*, who is genderqueer, this is a reality. “I don’t feel comfortable in thinking of myself as a girl, but then I don’t feel like I want to be a guy either. It’s kind of a sense of knowing it doesn’t ‘fit’, and feeling like I’m something different.”

Genderqueer people are neither male nor female and can feel that they belong to a ‘third’ gender, swing between genders or feel that they belong to none at all. LGBT charities estimate that one in 11,500 people experience some degree of gender variance in their lives, but genderqueerism is under-diagnosed.

Q for ‘queer’ or ‘questioning’ is a relatively new addition to the Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Transsexual banner, and even in LGBT support groups across the country, genderqueer people are a minority. If transsexuals are today what homosexuals were a decade ago – and still fighting for equality and recognition – then genderqueer people really are in uncharted territory, and fighting daily battles.

“You do experience hostility”, says Vic. “If people are confused about how you’re presenting yourself, that can often make them quite bizarrely angry. I do occasionally have people come up to me and say ‘What are you?’, but I tend not to get in a debate with them as I read it as quite a threatening situation”.

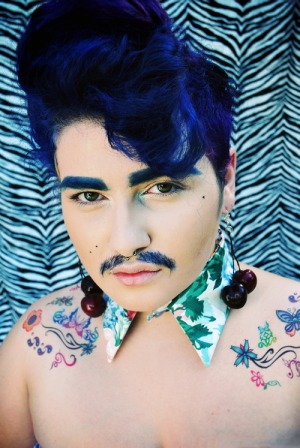

CN Lester, co-founder of the Queer Youth Network and founder of Britain’s first Gay/Straight Alliance, identifies as genderqueer and has also experienced aggression. “It comes very much from people who get angry because they can’t tell which side of the

fence you fall on, and they don’t want to feel that you’re confusing them and how they see the world. I’ve had quite a lot of street harassment, sexual harassment and some fairly nasty discrimination.”

Lester describes growing up as “feeling that something is up, that you often don’t feel right in your body or that you don’t understand your gender in the way that it’s presented to you by the world around you. It’s really hard when you don’t have the language surrounding that.”

For genderqueer people and the wider LGBT community, language is crucial in determining identity. Other terms for genderqueer include ‘non-binary gender’, ‘gender-fluid’ and ‘third-gender’, but what unites them all is that there is no definite catch-all term, and for many, no way of describing how they feel.

The use of pronouns is a sensitive issue. While it may seem pedantic to many, being described as a gender you feel worlds away from is distressing. Many genderqueer and androgynous people prefer the singular-plural pronouns of ‘they’, ‘them’ and ‘themself’, and in the burgeoning online genderqueer community, PGPs (‘preferred gender pronouns’) are paramount. One Google Chrome app, Jailbreak the Binary, even functions as a gender-neutral browser, replacing all gendered words and pronouns with gender-neutral ones.

Gender dysphoria is a medically recognised condition, and Bernard Rees, trustee of the Gender Identity Research and Education Society, says: “We use the term ‘gender variance’ which is discordance between the identity of the body and brain, and can be experienced at any time from the age of two. Nature is much more varied than one thing or the other -people can have a firm identity as a man or woman, or not quite as certain.”

Science has proven that there’s more to life than XX and XY chromosomes, literally, and although it’s important to differentiate between gender, the identity of a person, and sex, their genitals and physical make-up, genderqueerism and intersexuality often overlap.

Rees says: “There are about 20 or 30 different intersex conditions, and the neurobiological

variance in people shows there may also be biological factors at work in people’s gender identity.”

In the UK, the idea of a third gender is anathema to most people, and legal recognition of a third gender is virtually non-existent. In many other countries around the world, however, a third gender is recognised – both socially and legally – and even celebrated.

In India, hijra people are the most widely recognised third gender in the world, with up to six million in existence, three genderoptions on passport applications and third gender options on voter identity cards. In Pakistan, a 2009 census survey estimated up to 30,000 hijras in the country, and the Supreme Court ordered that a third gender be implemented on national identity cards, allowing them to apply for jobs.

Australia and New Zealand introduced an ‘X’ gender option for passports in 2011 and 2012 respectively, Argentina’s GenderIdentity Law of 2012 gave people the right to change their gender on documentation to the one they identified with, and as far back as 2007, Nepal’s Supreme Court added a third gender option to its census surveys and citizenship documents.

Indonesia, Polynesia and the Philippines have a long and accepting culture of a third gender, but England rugby player Manu Tuilagi’s Samoan third-gender fa’afafine sibling has been imputed in the British media as his “cross-dresser brother”. Compared to its global counterparts, Britain seems stuck in a binary-gendered bind.

Although some organisations such as the Department for Work and Pensions and the UK Deed Poll Service are all prepared to address a recipient using ‘Mx’ or ‘Misc’, they are yet to issue documents which legally confirm a third gender.

“I definitely don’t feel represented by the government when you only have two options to tick”, says Lester. “It would be a real step forward if there was Male, Female or Other. It’s interesting to consider whether we need to put Male or Female on passports at all. If we have a photograph, a date of birth, a name and increasingly, biometric data, it seems somewhat redundant to put an ‘M’ or an ‘F’ on there.”

Genderqueer groups in the UK have fought for third gender options on forms and documents, and many criticised the government for its lack of a third gender option on the 2011 census, despite a decade of campaigning. If third-gender people can’t even be counted in the census, then they will never be counted and identified as equal members of society.

“A charge so often levelled at people who are genderqueer is that we’re trying to make everybody like us, and I would hate that”, says Lester. “I’d hate to have a world full of people just like me, or just like everybody else, it would be boring as hell. But just accepting who we are, that would be really nice.”

*Vic did not want to reveal their surname